First checking that no one was watching him, Henry took a deep breath and knocked on the door. In fact, he was being watched by a neighbourhood cat (who felt nothing but pity for him), but he failed to notice this. I hope this was worth it, Henry thought, waiting for a reply. Inside the house, Karen waited for a second knock. Henry’s persistence was one of her favourite qualities. Henry shifted nervously and counted off the seconds until he got to thirty, then knocked again.

With a joyful yelp, Karen sprang from her chair and ran to the door. The crash it made as she flung it open was audible from one end of the street, where Mr Jameson was pensively watering his flower-beds, to the other, where Mary Simmons was lying in the bath and contemplating mortality. And so it begins, Mary thought to herself as Karen mentally browsed wedding dresses and Henry found his mouth growing dry. Three hundred miles away, Henry’s mother was unaware of any of this.

This is truly horrible; it makes my brain feel like it's in six places at once.

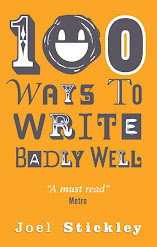

ReplyDeleteRe: a comic issue of How To Write Badly Well, I can kind of draw, and to demonstrate as much I did this sketch:

http://img33.imageshack.us/img33/9563/jhhu.jpg (it's not meant to be funny, just whatever words came into my head)

i could do better quality but can't promise I'd have the time to do so, so i thought I'd show an example I can definitely live up to

send me an email if you're interested

So bad it made me cringe - great job!

ReplyDeleteI kept wondering what the cat was thinking.

ReplyDeleteI'm sorry, but I find nothing wrong with this as I have an extremely short attention span and often

ReplyDeleteThe multiple POVs in the first paragraph actually aren't a problem. Omniscient-narrator narrative is out of fashion, but not therefore inherently bad writing. The problem in the second paragraph is that the POV switches lead the plot threads in too many directions at once, not that they exist at alli. Here's a seasonally appropriate paragraph by Dickens, a master of the style:

ReplyDeleteMeanwhile the fog and darkness thickened so, that people ran about with flaring links, proffering their services to go before horses in carriages, and conduct them on their way. The ancient tower of a church, whose gruff old bell was always peeping slily down at Scrooge out of a gothic window in the wall, became invisible, and struck the hours and quarters in the clouds, with tremulous vibrations afterwards as if its teeth were chattering in its frozen head up there. The cold became intense. In the main street, at the corner of the court, some labourers were repairing the gas-pipes, and had lighted a great fire in a brazier, round which a party of ragged men and boys were gathered: warming their hands and winking their eyes before the blaze in rapture. The water-plug being left in solitude, its overflowings sullenly congealed, and turned to misanthropic ice. The brightness of the shops where holly sprigs and berries crackled in the lamp-heat of the windows, made pale faces ruddy as they passed. Poulterers' and grocers' trades became a splendid joke: a glorious pageant, with which it was next to impossible to believe that such dull principles as bargain and sale had anything to do. The Lord Mayor, in the stronghold of the might Mansion House, gave orders to his fifty cooks and butlers to keep Christmas as a Lord Mayor's household should; and even the little tailor, whom he had fined five shillings on the previous Monday for being drunk and bloodthirsty in the streets, stirred up tomorrow's pudding in his garret, while his lean wife and the baby sallied out to buy the beef.

It's not everybody, perhaps, who can give a fire hydrant an inner life, but Dickens manages fine.

Hi John.

ReplyDeleteI will concede that omniscient narration is not in the realm of complete objective wrongness, but it is, in my eyes at least, a needless offence against style. To constantly push the narrative one way and another, jumping in and out of points of view like a season of Quantum Leap on fast-forward has a tendency to undermine the relationship between reader and text, weakening points of sympathetic engagement.

Whilst a 19th-century prose style still stands up in many respects, I would argue that the omniscient narrator is one vestigial feature we are better off without. Of course it is possible to use it well, but instances of this are so rare that it might be best to avoid it altogether.

As for Dickens, this passage is a great example of how he couldn't bear to miss an opportunity to insert sentimentality into his work – even his fire hydrants are martyrs!

All the best,

Joel

And note that Dickens doesn't give us his characters thoughts, just their actions. It's the narrator's emotion we get.

ReplyDeleteLol, that passage was hilariously bad, and good discussion on omniscient narration. I recently had some blog entries that you might find interesting. One is on Neil Gaiman headhopping in the Graveyard book, and the other one is a discussion about why it's not popular anymore. I'd love to hear your thoughts!

ReplyDeleteParody of post-modern transcendentalish art? I love that I now have the words to describe this technique, for when it goes horribly wrong (and it soooo goes wrong). Also, you're hilarious. This blog is going to be great for my writing (hopefully keep me from writing such crap, and from overusing parentheses).

ReplyDeleteHeadhopping only hurts the head of the reader. Which, duh, is what you're after, right? Why hurt a poor reader's head? Why???

ReplyDeleteHere's what Ursula K. Le Guin says in her subversive manual of fiction writing, Steering the Craft, about what she calls "involved author" voice:

ReplyDeleteThe story is not told from within any single character. There may be numerous viewpoint characters, and the narrative voice may change from one to another character within the story, or to a view, analysis, perception, or prediction that only the author could make. (For example: the description of what a person who is quite alone looks like; or the description of a landscape or a room at a moment when there's nobody there to see it.) The writer may tell us what anyone is thinking and feeling, interpret behavior for us, and even make judgments on characters.

This is the familiar voice of the storyteller, who knows what's going on in all the different places the characters are at the same time, and what's going on inside the characters, and what has happened, and what has to happen.

All myths and legends and folktales, all young children's stories, almost all fiction until about 1915, and a vast amount of fiction since then, use this voice.

I don't like the common term "omniscient narrator", because I hear a judgmental sneer in it. I think "authorial narration" is the most neutral term, and "involved author" the most exact.

Limited third person is the predominant modern fictional voice — partly in reaction to the Victorian fondness for involved-author narration, and the many possible abuses of it.

Involved author is the most openly, obviously manipulative of the points of view. But the voice of the narrator who knows the whole story, tells it because it is important, and is profoundly involved with all the characters, cannot be dismissed as old-fashioned or uncool. It's not only the oldest and most widely used storytelling voice, it's also the most versatile, flexible, and complex of the points of view — and probably, at this point, the most difficult for the writer.

In the same book, Le Guin gives the reader the same paragraph from a story called "Princess Sefrid" using different standard voices, but all firmly 20th-century. Here they are:

ReplyDelete[First person narrator.] I felt so strange and lonesome entering the room crowded with strangers that I wanted to turn around and run, but Rassa was right behind me, and I had to go ahead. People spoke to me, asked Rassa my name. In my confusion I couldn't tell one face from another or understand what people were saying to me, and answered them almost at random. Only for a moment I caught the glance of a person in the crowd, a woman looking directly at me, and there was a kindness in her eyes that made me long to go to her. She looked like somebody I could talk to.

[Limited Third person.] Sefrid felt isolated, conspicuous, as she entered the room crowded with strangers. She would have turned around and run back to her room, but Rassa was right behind her, and she had to go ahead. People spoke to her. They asked Rassa her name. In her confusion she could not tell one face from another or understand what people said to her. She answered them at random. Only once, for a moment, a woman looked directly at her through the crowd, a keen, kind gaze that made Sefrid long to cross the room and talk to her.

[Involved author.] The Tufarian girl entered the room hesitantly, her arms close to her sides, her shoulders hunched: she looked both frightened and indifferent, like a captive wild animal. The big Hemmian ushered her in with a proprietary air and introduced her complacently as "Princess Sefrid" or "the Princess of Tufar". People pressed close to meet her or simply stare at her. She endured them, seldom raising her head, replying to their inanities briefly, in a barely audible voice. Even in the pressing, chattering crowd she created a space around herself, a place to be lonely in. No one touched her. They were not aware that they avoided her, but she was. Out of that solitude she looked up to meet a gaze that was not curious, but open, intense, compassionate — a face that said to her, through a sea of strangeness, "I am your friend".

[Detached author.] The princess from Tufar entered the room followed closely by the big man from Hemm. She walked with long steps, her arms close to her sides and her shoulders hunched. Her hair was thick and frizzy. She stood still while the Hemmian introduced her, calling her Princess Sefrid of Tufar. Her eyes did not meet the eyes of any of the people who crowded around her, staring at her and asking her questions. None of them tried to touch her. She replied briefly to everything said to her. She and an older woman near the tables of food exchanged a brief glance.

[First person observer.] She wore Tufarian clothing, the heavy red robes I had not seen for so long; her hair stood out like a storm cloud around the dark, narrow face. Crowded forward by her owner, the Hemmian slavemaster called Rassa, she looked small, hunched, defensive, but she preserved around herself a space that was all her own. She was a captive, an exile, yet I saw in her young face the pride and kindness I had loved in her people, and I longed to speak with her.

(Le Guin also gives a third person observer version, but it's not available online.)

Now each of these reveals and conceals certain things, but consider just the one sentence "They were not aware that they avoided her, but she was." Only the involved author can possibly make that contrast; none of the other voices are capable of pointing it out.

And one last bit, Le Guin on the downside of the omniscient narrator:

ReplyDelete[T]he involved author can move from one viewpoint character to another at will, but if it happens very often, unless the writing is superbly controlled [...], readers will tire of being jerked from mind to mind, or will lose track of whose mind they are supposed to be in.

Particularly disturbing is the effect of being jerked into a different viewpoint for a moment. The narrative is being told from inside Aunt Jane's viewpoint. Then for one sentence we're in Uncle Fred's viewpoint. Then we snap back into Jane's. With care, the involved narrator can do this (Tolkien does it with the fox). But it cannot be done in limited third person. Remember when [in an earlier chapter] Delia raised her violet eyes? That was a one-word POV shift. It doesn't work.

[...]

So you can shift from one viewpoint character to another any time you like, if you know why and how you're doing it, if you're cautious about doing it frequently, and if you never do it momentarily.

[End Le Guin quotations]

Which was your point.

Yes, this is why Ulysses is so universally hated, I guess

ReplyDeleteI mean, it's not easy to do, so I guess bad writers would try it and be garbage at it, but still.

After all the above posts, I'd like to tell THE.EFFING.LIBRARIAN that I share her problem with the sort attention span, which Le Guin and Dickens obviously

ReplyDeletego to the website best replica designer bags look at this website replica bags buy online more info here replica designer backpacks

ReplyDelete